Mental Models for Crypto

Where finance and organization in our society is headed, and why you should pay attention

I’ve written about the history of money before — but I feel like it’s important to put this in context of relatively recent advancements in bitcoin and cryptocurrency. I’m going to do this with the help of a fictional country that captures the major payment systems of the world and their evolution over time.

This blog should give you a sense of currencies past and present, and help you think about the future of financial systems and, more broadly, human coordination. This post strives to convey broad ideas, rather than precise details behind all the various systems discussed. I try to keep the language basic, so a non-techie, non-cryptobro, non-economist can get a feel for the broad ideas behind these exciting new technologies.

So, what is covered in this post?

Old Money — Here we’re setting the scene with a brief discussion of traditional currencies and cash systems

Digital Money — With the invention of the internet came a need and the ability for digital exchange of value

Towards Decentralization (of digital money) — Here we discuss the motivations behind a decentralized money system

Peer-to-peer money (blockchain) — Next, we look at blockchains and the broad ideas behind it

Looking forward — This is the final part where we tie everything together and discuss what it means for financial systems, for civilization builders and more broadly, for human societies…

Let’s dive in!

Old money

Imagine an island state Monetopia that prides itself on having the most secure and functional payment systems in the world.

Prehistoric money in this land was mainly characterized by some form of debt or barter systems, but with very few written records (writing was only invented around 3500 BC), we can only guess.

Monetopia created the first formal payment system in about 700 BC with the invention of currency — state-issued and standardized coins and banknotes to exchange value and conduct trade. Fascinatingly, it’s possible that this was issued by the state (government) to solve the problem of maintaining standing armies in imperial empires.

Need for Global Currencies

Over the next 2 millenia, transport systems in the world evolved and cross-border trade became a crucial part of the world economy. In such a system, there were lots of local currencies that had very little value or acceptance in other parts of the world. So major world governments came to print currencies in precious metals like Gold and Silver. These were universally valued and seemingly scarce resources. Over time, with increasing standardization, the largest economies of the world adopted the Precious Resource standard, where their money supply (amount of money printed) was tied to their reserves of a scarce precious resource — a rare physical element of significant perceived value.

This served well as a native currency system for exchange until the 1960s, when computers and the internet were introduced to the economy. Information could now travel at the speed of light, and a lot of the time of inhabitants in the economy began to be spent in the digital sphere. This necessitated the creation of faster means of money movement, to keep up with near-instantaneous transfer of value that could now occur online.

Digital Money

So over the next 30 years, the monetary authorities created digital money, gradually removing a large percentage of physical money from the economy to be replaced by its digital counterpart.

What is digital money, really?

Note that money can simply be thought of as a system of accounts that keeps a common store of everyone’s balances in the system. That’s it!

So digital money is just a digital system of accounts where the central bank of the country keeps the common record — a track of who owns what in the economy. This system is federated — the central bank keeps track of which banks own what, the banks keep track of which individuals and companies own what, etc.

Printing: The central bank was already responsible for printing physical money historically, so they just became custodians of this digital money system and controlled the printing of digital money

Transfer: As opposed to passing around physical banknotes, transferring money is now done with an update to this system of accounts. (If I pay you 10 units of money, the banks in the system update the record such that I now own 10 less and you own 10 more).

The banking system introduced online payments and credit cards, where users could authenticate with their banks and pay/get paid, entirely online. If Alice wants to transfer 10 units of money to Bob, it is a simple process consisting of four parts:

She signs an electronic document or note and gives it to her bank, to authorize the payment

Her bank updates that Alice now owns 10 fewer units, and informs the central bank that it needs to pay Bob at Bob’s bank

The central bank updates its systems to reflect that Alice’s bank owns 10 fewer units and Bob’s bank owns 10 more units, and sends a confirmation to Bob’s bank

Upon confirmation of this receipt of the money from Alice’s bank, Bob’s bank updates Bob’s balance to reflect 10 more monies

Online payments and transfers became such a convenient mode of exchange that these significantly outpaced the growth of physical banknotes, so much so that Monetopia today only has under 10% of their currency in physical cash.

Towards Decentralization

One day the government of Monetopia, along with other governments in the world decided to take themselves off the prevailing Precious Resource standard. This scared the inhabitants of Monetopia for various reasons that included the already well known drawbacks of centralized digital money systems:

The centralization of the money supply allows governments to create money from scratch, such as sometimes creating almost 3x the total money in circulation to finance relief programs during economic downturns

Even if their own government played honest, they frequently conducted trade with other economies of the world and a lot of their citizens owned money in many different local currencies. These other governments may print money arbitrarily, causing a devaluation of their citizens’ ownership of those currencies

Other existing problems like centralized stakeholders being able to monitor and censor transactions

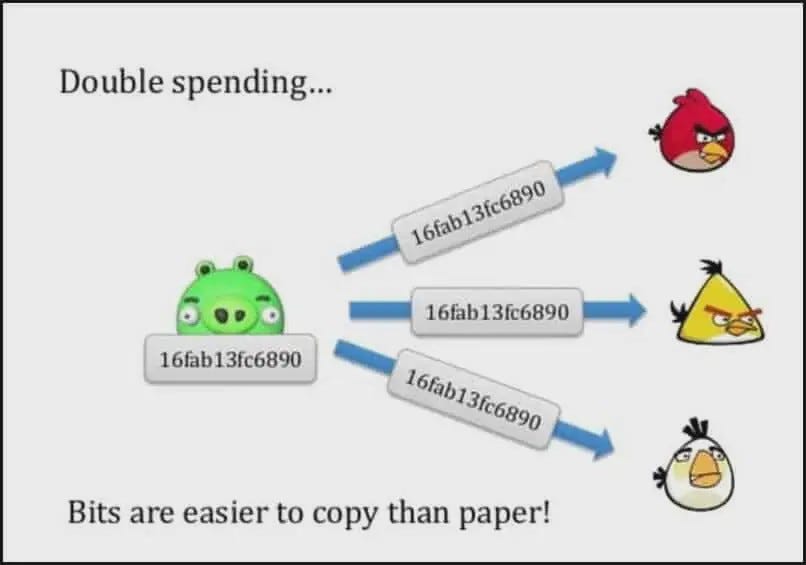

Double Spend

For reasons mentioned above, Monetopia’s inhabitants wanted a decentralized (does not require a trusted third party) and censorship-resistant digital cash system that was not controlled by the government or any single institution.

There’s one problem with representing money as ‘information’ in the digital world — if I send you my mp3 file, I still have a copy. So if I was assigned a naive digital ‘banknote.csh’ file, I could send it to Bob in exchange for bread, and then send it to Carol in exchange for milk (and still have the banknote.csh file!).

Note that in previous systems — physical currency and digital money — this ‘double spend’ problem did not exist.

In the case of physical banknotes — once you transfer cash from your hand to another, it no longer exists in the previous hand so the original owner can only spend once

In the centralized digital system there is a central bank that keeps a record of everything that everyone owns

So if I wanted to spend the same amount of money twice, they would only allow the first transaction to be successful

Decision by majority

Now, maybe one way to solve this problem would be to have everyone vote on new transactions and use a majority to decide if a record should be added to the account-book.

But the problem with this is that in an online world, it is very easy for someone to pose as many people (by spawning multiple virtual machines from various IP addresses) — therefore gaining more voting power in a simple majority system.

Peer-to-Peer Money

If not by simple majority, how can you allow computers to achieve consensus (i.e. agree on the correct set of transactions) in this system? You need at least two things:

to solve the problem of digital duplication

A way for everyone to agree how to add new transactions

Turns out this is a serious problem and one that took the inhabitants of Monetopia several decades to solve. But one day a brilliant citizen scientist from Monetopia came up with a scheme to solve this problem.

This new scheme solves the first problem by stating that any participant in the network has to solve a provably difficult problem in order to gain the ability to add a (valid) transaction to the system. The second problem is solved by chaining these transactions together and everyone agreeing that the longest chain of transactions is the most valid one. The result? A distributed ledger of transactions that is controlled by no-one and can be trusted by all participants in the network.

To summarize - so far we’ve seen:

Finally these technical solutions are combined with economic incentives for participants to maintain the network and process transactions. This enables massive coordination at scale without requiring a trusted third party to organize.

I’d detailed out (diagrams and everything) 2 different analogies to explain this scheme in more detail here, but turns out it’s just a little too involved to explain in this post. But if you’re interested in the real nuts-and-bolts behind this technology — there are good explainers here, here and here.

However, if there’s one thing that you should absolutely take away from this section — it is the simple mental model that the new technology allowed citizens to maintain a common record that everyone could trust, and no one-person could control. This common record can store anything — transactions, code, media, generic files, etc.

Looking Forward

Okay bringing this back to the real world — the new system was developed by Satoshi Nakomoto and is called Bitcoin, and the technology underpinning it is the blockchain. While Bitcoin was a first application that just kept track of balances in the common record (and therefore is just a currency system), other projects, such as Ethereum, came along that allowed programmability on these balances, and opened the door to a plethora of new use cases.

Coordination and Trust

First, let’s take a little step back and evaluate how far we’ve come.

Throughout the history of humans, trust has always preceded coordination. If I was going to hunt a bear with you (and hopefully some more people), I had to be sure that you wouldn’t leave me to die if the bear got irrationally pissed at my attempts to kill it. These were simpler hunter gatherer times (only about 15,000 years ago), and we lived in small groups or tribes and shared close bonds with members of our own community. But there is a limit to how many people you can build these bonds with over the course of your lifetime, constrained by time and reach.

As societies progressed and large cities and kingdoms came about, we needed the ability to coordinate and collaborate at scale. How do you get so many people to trust each other? You create centralized institutions — kings, republics, corporations and financial institutions. You trusted one of these institutions and they provided you some combination of peace, security, convenience, comfort and leadership. These institutions became brokers of trust, and therefore gained immense power in the process.

For example, governments maintained peace and security within their dominion, and in turn collected taxes and wielded near absolute power over their citizens.

Today with blockchain technology, for the first time in the history of civilization, coordination can come before trust. This is because you can bake in incentives for people to come together to build something bigger than themselves, and be financially rewarded in the process. This is a powerful concept — with blockchains, people don’t put their trust in individuals — they rely on mathematics and every other human’s rational self-interest. If you’ve heard blockchains described as trustless before, this is what that means.

As an example, the entire Bitcoin network is a coordinated effort by participants who don’t know each other, let alone trust, to come together to maintain a transaction processing system. Another blockchain, Arweave, is a coordinated effort by participants in that system to recreate the library of Alexandria — i.e. to become a persistent store of all the knowledge in our society.

Taking this a step further, Decentralized Autonomous Organizations (DAOs) are applications being built on programmable blockchains like Ethereum. DAOs are a new way to coordinate people where voting power is based on their ownership in an underlying protocol. Since anyone with an internet connection (which is nearly 5 billion people) can participate in such an effort, this unlocks the ability to scale coordination to civilization-scale. This ability to coordinate has profound implications for governments, countries and monetary systems of the future.

As an example, MakerDAO is a decentralized organization behind the Maker protocol, which intends to create a stable currency on the internet. Recently, another decentralized organization named ConstitutionDAO got together to purchase a copy of the US constitution — granted they narrowly lost to a billionaire hedge fund owner, but it represents the ability for people that cared about the same goal to get together without necessarily trusting each other.

Imagine a DAO that intended to push the frontiers of human progress in the twin spheres of culture and science — people could get together to prioritize goals, actions, incentives and workers.

One Bank for All

Apart from scaling coordination, a lot of financial infrastructure that existed in the physical world is now being built for the decentralized world. If you’ve ever seen the HBO show Deadwood, which depicts the birth of a city during a gold rush in the late 1800s — you realize that a bank is a critical piece of infrastructure in any new economy.

But if that was playing out today, we would probably have a lot of the physical infrastructure — hardware shops, doctors, bars, hotels — but probably not a physical bank. Banks are a relic of the age of atoms! We are living now in the world of bits and information — and here we do not need physical banks anymore. Enter Decentralized Finance (DeFi).

What is decentralized finance?

Imagine if everyone in the world had the same bank that was designed to be open-source (open, community designed), operated by code and owned by everyone. What does that look like?

full control of their own wallets and instant access to their money for everyone, everywhere, everytime

full visibility and execution guarantees on the bank’s code

gives every individual the ability to pool their assets and collateral in a common place

globally pooled capital for scalable and cheap lending and borrowing

globally pooled liquidity for exchanging between different cryptocurrencies

Why I’m Excited

All of the above gives us plenty of reasons to be terribly excited!

In addition, what is really interesting here for me personally, is the fact that there is so much white space to explore and build in the near future. It will probably take another decade or two before the fairy dust settles on the best protocols, the best designs, and the best practices and global currencies.

For example, decentralized finance protocols like Compound are rewarding their lenders and borrowers with stake in the protocol itself. It’s like every time you made a deposit in your bank, you also received a small share in the bank itself. This is a new form of incentive design that is enabled by programmable blockchains!

While we are waiting for these fancy incentive schemes and their underlying protocols to stabilize in the coming decades, this is a once-in-a-generation opportunity to do real groundbreaking, zero-to-one work for all builders and entrepreneurs in tech.

The fact that these technologies are permissionless also means that recent attempts by centralized institutions to censor this will only accelerate the paradigm shift. Cryptocurrency is at a stage where it is nearly uncensorable. If economies of the world wanted to ban Bitcoin and crypto, they should have done it back in 2010.

What happens when an unstoppable force meets a slow-moving object that does not understand it? It simply goes around.

That’s it for now. If you’re also excited about this space feel free to DM me or reach out on LinkedIn/Twitter!